Active, Reference, Ground

The active, reference, and ground are three different types of electrodes that are combined to provide a single channel of EEG. This is because EEG is always recorded as potential for current to pass from one electrode (active) to usually a ground electrode (Luck, 2014, Chapter 5). If this concept of electricity and magnetism is confusing, I highly recommend reading Luck’s second chapter “A Closer Look at ERPs and ERP Components”. The term “absolute voltage…refer[s] to the potential between a given electrode site and the average of the rest of the head”, (Luck, 2014, Chapter 5). What this means is that the potential between the active electrode and the ground electrode is simply the difference between these two absolute electrodes. If you are familiar with basic physics, then you can understand why there is no voltage at a single electrode: you have to have voltage from two sources for everything because voltage is the potential from one source to another.

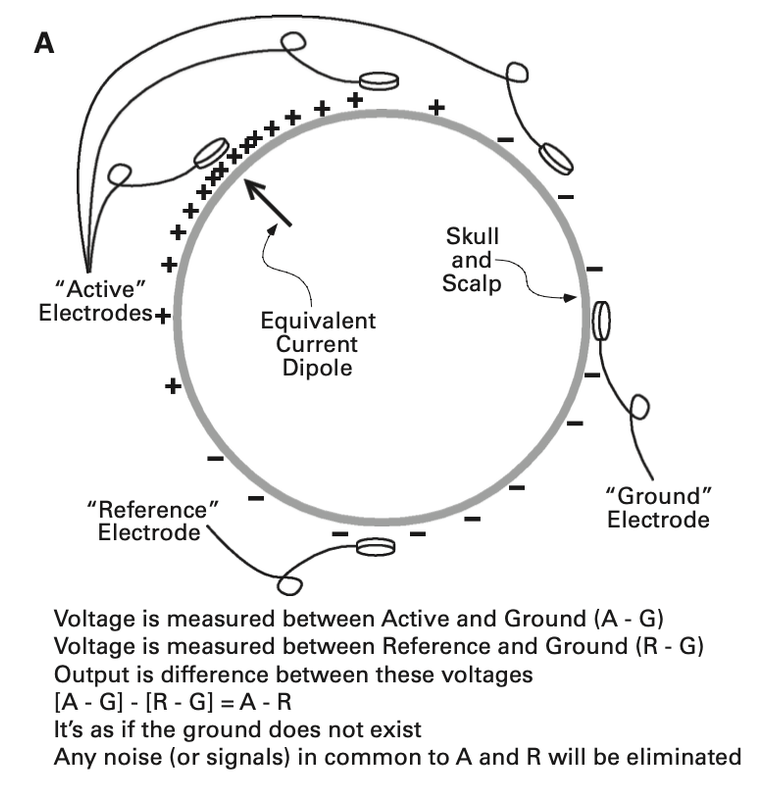

For some background when describing the reference electrode, it is important to know that EEG recording systems typically solve the problem of noise in the ground circuit by using what are called differential amplifiers (Luck, 2014, Chapter 5). The reference electrode, in theory, is supposed to be away from the brain activity we are directly measuring, using it to subtract from each active and ground electrode. This makes sense practically, as we are creating a sort of baseline for recording neural activity in order to get rid of any common noise. Here is a section from one of the figures used from Luck in the fifth chapter, that helped me understand this concept:

The purpose of the ground electrode can be described as “when voltage is initially measured between two electrodes, one of the two electrodes must be connected to the amplifier’s ground circuit, and this circuit picks up noise from the amplifier circuitry”, (Luck, 2014, Chapter 5). You also may now be wondering why we can’t record the voltage directly between the active and the reference, but the reasoning for this is because “without connecting R to the ground circuit (in which case it would simply be the ground electrode). Thus, most systems use a differential amplifier to cancel out the noise in the ground circuit”, (Luck, 2014, Chapter 5).

To tie all these concepts together, you should know that “the electrical potential between the subject’s body and the amplifier’s ground circuit is called the common mode voltage (because its common with the active and ref electrodes)” and that “to achieve a clean EEG recording, this common mode voltage must be completely subtracted away”; however, this is not as perfect in implementation (Luck, 2014, Chapter 5).

For practical implementation of these ideas: the location of the ground electrode is trivial, so feel free to place it anywhere on the head. However, the site of the reference electrode requires a little more thinking. Luck provides some advice: “given that no site is truly electrically neutral, you might as well choose a site that is convenient and comfortable”, “also close to the site of interest and one that other researchers use”, and “you want to avoid a ref site that is biased toward one hemisphere”, (Luck, 2014, Chapter 5). I would recommend for our purposes to place your reference on the electrode on the mastoid(s) to stay consistent with other researchers.